Foundations

Women-Centred Housing Design: Foundations

The question of ‘What is a women-centred housing?’ led the BCSTH consultations.

Through our consultation with the anti-violence and housing sectors and women with lived experiences of violence, key tenets arose that define women-centred housing. From the perspective of the anti-violence sector and women with lived experience, women-centred housing recognizes that women with/without children/dependents after leaving temporary housing and programs are at risk of homelessness, housing precarity, and violence and live with the realistic fear of these outcomes.

Women-centred housing incorporates an intersectional lens and recognizes the intersecting social identities that may lead to housing inequalities and prioritizes affordability and adaptability to the unique and ever-changing needs of women and their children. It also values women’s significant role in determining their housing space design interventions, policies, and procedures.

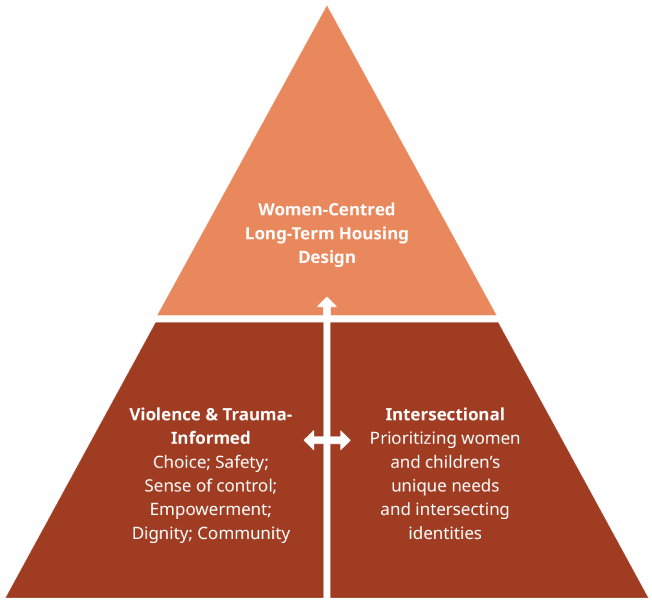

Women-centred housing embodies a violence- and trauma-informed approach in both space design and operation to reduce potential triggers and facilitate healing for women and their children/dependents after violence. It emphasizes safety and security, cultural safety, community, dignity and self-esteem, and residents’ well-being. Figure 10 shows these two core foundations that long-term women-centred housing is built upon: Intersectionality and Violence- and Trauma-Informed.

Figure 10. Core Foundations

Violence and Trauma Informed Design

Built environment and housing has an impact on our physical and mental health. Violence and trauma-informed design is based on an understanding and responsiveness to the impacts of trauma on individuals. It emphasizes safety (i.e., emotional, physical and physiological), choice, and creating opportunities for healing, connections, and rebuilding sense of control, and empowerment for survivors (Hopper et al., 2010; Shopworks Architecture et al., 2020). Having an understanding of trauma in designing housing is crucial because of the environmental triggers that may impact the experiences of users in the space. Aspects of an environment that may be triggering include disruptive sounds (e.g., footsteps, doors slamming), unpleasant scents (e.g., cigarette smoke, perfumes), lack of security for self and belongings (e.g., open windows, broken security cameras), visual noise (e.g., lack of exits, unclear wayfinding), uncomfortable sensations (e.g., no adjustable thermostat, narrow hallways, no fresh air), and institutional materials (e.g., fluorescent lights, ceiling tiles, generic furniture) (Grabowska et al., 2021). Therefore, violence- and trauma-informed design aims to mitigate these impacts through improving housing qualities and an understanding of sensory effect of space and materials, and as a result enhance the experiences of the users in the space.

Trauma can be the outcome of different violent and traumatic experiences (e.g., physical injury, post-war trauma, gender-based violence). In the context of this toolkit, women’s experiences of intimate partner violence and its impacts on them and their children/dependents guides these housing design solutions and is why we use the term “violence- and trauma-informed” design. In this regard, involvement of the anti-violence sector and consultation with women with lived experiences of violence have been a critical part of developing this toolkit. Women with lived experiences informed the creation of this toolkit by identifying what is triggering or healing for them in their living spaces. Also, the critical lens that the anti-violence sector brings from their experiences of operating and building both temporary housing programs and long-term housing has been essential as they recognize the impacts of trauma and violence on women and their children/dependents. For example, women’s experiences of male violence are often a reason why many women want to live in a women-only living environment in the short or even long term. Also, experiences of violence can result in women’s enhanced needs for feelings of safety and security in their home environment and their need for supports from the community. Design ideas and strategies in this toolkit seek to improve feelings of housing safety, minimize the risk of conflicts between residents, break the isolation, and provide a healing environment where women and their children/dependents rebuild their sense of safety, dignity, empowerment, and control and overall improved well-being.

Intersectional Design

Intersectionality (later redefined as intersectional feminism) is a term coined by American civil rights advocate, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1991, to describe intersecting social identities (e.g., gender, culture, ethnicity, ability, race, immigration status) and related systems of inequalities, oppression, and discrimination (Crenshaw, 1991; Sauer, 2018). Intersectional design recognizes that the many intersecting identities that individuals have, result in multiple sites of marginalization and oppression (Denicola et al., 2021). The WCD project recognizes the distinct ways these social identities intersect and influence women and children’s unique housing needs and experiences. Therefore, engaging women with lived experiences was a key component of this project to capture their unique needs and the inequalities they may experience in housing. For example, gender, family size and composition are some of the important identities that impact the needs of women and their children. Also, being the primary caregiver to their children/dependents is the reality for many of women with lived experiences of violence. As a result, these roles and identities being reflected in the design of spaces becomes important. One of the examples of reflecting these identities and roles in spatial design is through providing natural surveillance/the ability to observe their small children playing in the playground while doing other tasks in their apartment unit.

These identities and needs require a gender-sensitive lens to space design. Design of built environment, including housing and neighbourhood public spaces, are gender-sensitive if they are inclusive and equitably meet the needs of different life phases and realities (City of Vienna, 2013). Therefore, a level of flexibility and adaptability in the design and potential use of their housing environments will be required in order to meet the needs of children and women at different life stages (Isthmus Group Ltd, 2018). Flexibility gives women and their children choice as to how they want to use spaces instead of architecturally predetermining their lives. Flexibility of housing spaces also benefits the housing providers in the long term by leading to less occupant turnovers and the ability to react quickly to changing needs of existing and potential future inhabitants with minimum costs (Schneider & Till, 2005).

Hierarchies and imbalances in housing unit spaces were caused by the design of housing based on the structure of a typical nuclear family with traditional distribution of roles between men and women (Montaner et al., 2019). Research shows that many gender-neutral housing and support services have been built upon the experiences and needs of cisgender men. As a result, there is a gap in many communities for adequate housing and services for women and gender diverse people (Milaney et al., 2020). The design approach offered in this toolkit recognizes the intersecting characteristics of the household including age and gender of children, family size, single parenting and acknowledging the varied roles that women play in the family and home. Taking a gender-sensitive approach leads to designing housing that reflects these varied roles and responsibilities and creating more ease for women. It allows women and children to remain in their home and/or neighbourhood, instead of moving out, during different stages of life, such as when children grow up, move out, or when women have their children living with them as a result of unification. When women have the choice of remaining in their housing and neighbourhood, it fosters a sense of community belonging and feelings of housing stability for them.

Flexibility and gender-sensitivity are two related concepts due to the evolution of housing in a society with a variety of different family structures as well as the demand for gender equality. Gender-sensitive housing minimizes hierarchical traditional design assumptions to mitigate the gender inequalities. A non-hierarchical home does not have rooms that are larger and have better qualities than other spaces (Montaner et al., 2019) but considers the families’ actual priorities and life pattern in the design. Anti-violence stakeholders confirmed this in consultations contributing that more considerations need to be given to the ways women with children live in the space.

“There is too much focus on the bedroom as the sanctuary and shared amenity room as the main place to socialize. But, there needs to be enough space in the living room area within the unit that can accommodate children’s indoor plays and socializing within the family. Distribution of spaces in all the housing units based on a large primary bedroom, a small second bedroom, and small living room do not necessarily work for everyone. Instead, there should be diversity in the types of units and a right balance between unit design size and common spaces.”

– Anti-violence Stakeholder

Levels of flexibility in designing women-centred housing will enable personalization and utilization of space based on cultural and lifestyle preferences for households as well. If households are not allowed to customize their living spaces as per their own lifestyle and cultural needs, it can result in mental dissatisfaction that may lead to irritated and hopeless mentality (Rian & Sassone, 2012). Women with lived experiences of violence and anti-violence professionals shared that cultural identity and lifestyle preferences are other important intersecting factors to reflect in the design of housing. Research shows that Indigenous and immigrant individuals are more likely to live in intergenerational families due to their family size but also because of the economic and social benefits of living communally (e.g., more affordable, care for children and seniors, connection) (Butler et al., 2017; Labahn & Salama, 2018). Housing spaces that recognize the importance of culture and cultural needs and practices help families to feel a sense of dignity and belonging. It also empowers them by giving them choice to personalize their living spaces based on their lifestyle preferences which is a vital component of violence- and trauma-informed design.