Principles

Women-Centred Housing Design: Principles

The Toolkit’s main design principles for women-centred long-term housing were guided by consultations with women with lived experience and housing and anti-violence professionals. Our research and findings conclude that housing spaces for women and their children/dependents after violence should

-

Reflect safety and security in design

-

Allow for convenience and efficient use of space and easy access to services (e.g., childcare, transportation, food resources)

-

Incorporate homelike features and access to natural/green spaces

-

Provide and, bring comfort

-

Be accompanied by support services and spaces for community building

These principles and their corresponding strategies and actions meet the psychological, spiritual, and material needs of women and children and reflect the two core foundations of women-centred design discussed above (i.e., Violence- and trauma-informed, Intersectionality).

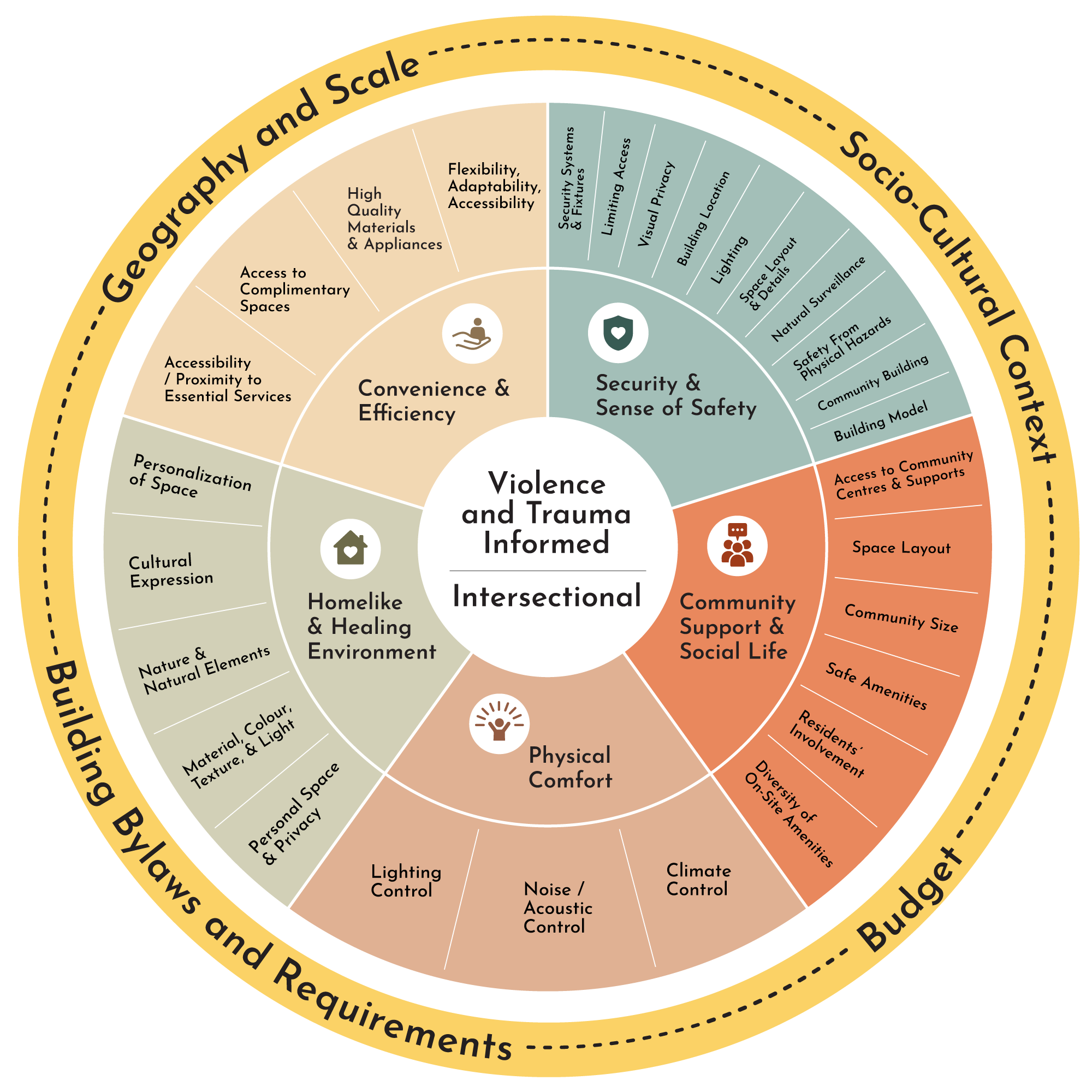

Figure 12: Women-Centred Housing Design Model

Figure 12 shows the main principles and corresponding strategies of women-centred housing design and its core foundations. This model also shows the contextual and external factors that impact feasibility and applicability of the design ideas which are explained in the Feasibility section of this toolkit.

Women-Centred Housing Design: Spatial-Scale

The principles, strategies, and actions in the toolkit can be applied to a variety of housing including small buildings, townhouses, and multi-unit housing (e.g., low-, medium-, and high-rise). Users of the toolkit will be able to incorporate and adapt the toolkit elements to fit their housing projects.

The design ideas are offered in 3 spatial levels: in-unit, in-building (common area and amenities), and the way housing connects to its immediate neighbourhood (Figure 13). These scales highlight the importance of not only on-site space design which are private and semi-private territories, but also connection to the neighbourhood that relates to the site selection, evaluation and nearby services. The literature discusses these spatial scales as essential scales of housing design for women and children with experiences of violence and homelessness (Sprague, 1991; Vaccaro & Craig, 2020; Zinni, 2019).

Security & Sense of Safety

The top priority in the design of long-term housing for women and their families…

Convenience & Efficiency

Access to services and efficient use of space cultivates peace of mind for women and their children…

Homelike & Healing Environment

Women-centred housing is a welcoming and joyful environment that feels non-institutional…

Physical Comfort

Physical comfort includes physical relaxation and without environmental concerns and triggers…

Community Support & Social Life

Access to on-site services has been identified as beneficial, in addition to public spaces to connect…

Feasability & Applicability

This project identified some contextual and external factors which may impact the feasibility and applicability of implementing the women-centred design strategies and actions. These factors also contribute to customizing the strategies offered in the toolkit by housing providers, developers, and designers according to what is most appropriate and applicable in each housing project context. These factors include geography and scale, budget, building bylaws and requirements, and socio-cultural context. Housing providers and professionals need to adapt the design strategies based on these considerations. The Toolkit also provides recommendations to funding organizations and municipal and provincial bodies on how to support the implementation of strategies that support women-centred housing.

Geography and Scale

Implementing the women-centred housing principles and strategies varies according to geography and scale of the communities. The regional differences in adopting the suitable design strategies are impacted by environmental factors such as climate (e.g., long winter season), topography of the area, and environmental and natural disaster risks (e.g., flood, wildfire). Differences in adopting women-centred housing design strategies are also impacted by the size of the community and housing types, and the regions’ access to human resources (e.g., fewer contractors, skilled labourers in rural and remote communities). Some members in rural and remote communities shared that they faced challenges hiring contractors which resulted in extending the time of development, and also the ability to maintain and sustain some of the installed housing infrastructure (e.g., smart building systems) due to lack of locally skilled laborers to maintain them.

Furthermore, a lack of transportation options (e.g., public transportation, car share programs) in proximity of housing projects in rural and northern communities limits the ability of housing providers to locate housing projects in areas that have easy access to resources. As a result, design actions (e.g., related to this strategy – for example, Access/proximity to essential services) becomes beyond the housing providers’ power and need to be addressed by local governments. An example of this approach is the BCSTH Transportation Project focused on embedding a Gender-Based Approach in Northern and Rural Transportation Systems

Socio-Cultural Context

Socio-cultural factors (e.g., lifestyle, demographics) may vary in each community, which impact the relevance of various housing design strategies in each community and the way they get adopted and integrated into the final housing design. Intersecting identity factors (e.g., values, demographic characteristics) and the lived experiences will define preferences and practices in each community. As a result, reflecting them in the adoption of design strategies will contribute to more suitable and culturally appropriate women-centred housing. For example, housing projects intended to house Indigenous women and children requires design strategies and spaces to support cultural safety and their cultural practices and needs. An example of this approach is the Cultural Safety Project by the Aboriginal Housing Management Association (AHMA).

Budget

Members and housing professionals shared that the ability to implement women-centred design principles in their housing projects is significantly impacted by budget constraints and access to development funding. For example, incorporating security systems which may enhance a women’s sense of safety, may not be in the original budget and represent a significant cost increase potentially. BCSTH members reflected that they had to forego design elements that achieved home-like qualities in order to cover the primary costs of development. Limited funding and cost increases have been major reasons that the final housing designs vary from the women-centred housing design they had originally envisioned. In addition, site selection is another barrier in developing affordable housing for women and their children as locations with easy access to resources are often expensive and beyond the resources of the housing providers.

Building Bylaws and Requirements

Members stated that some of the building design requirements and bylaws from provincial and municipal entities and funding agencies (e.g., CMHC, BC Housing) are not feasible in some communities. BCSTH members in rural and remote communities advised that they would have approached the design differently to meet the needs of women and their families.

Recommendations

These recommendations are provided to support the implementation of women-centred design strategies and address the challenges identified in the Toolkit consultations.

Funding Availability

Funding agencies and federal and provincial bodies (e.g., CMHC, BC Housing) that partner with member organizations and housing providers to develop women-centred housing should recognize the costs associated with integrating women-centred housing design principles. They should ensure that these costs are included in their funding formulas and consider the varied needs and challenges of certain communities, such as the extra costs associated with construction in rural and remote communities compared to urban areas.

Flexibility in Design Requirements

Funders and provincial bodies should engage with housing providers and BCSTH members in order to develop women-centred housing and be flexible and responsive in design priorities, allowing members to identify the essential elements and those that are not violence- and trauma-informed in their housing projects.

Reflecting Women-Centred Design Principles and Strategies in Family Housing Guidelines

Provincial and municipal organizations who provide requirements for the design of family housing should include the recommendations of women-centred housing design in their guidelines.

Engagement of Women with Lived Experiences in Housing Design

In order to meet the specific needs of the community, housing providers should engage women and children with lived experiences of violence in the process of designing and prioritizing their women-centred design strategies.